In December 2015, I returned to Paris — a city I’ve loved for as long as I can remember. This visit was different. It came a little more than a month after the November attacks, when coordinated shootings and bombings struck the city, including the Bataclan concert hall. Many lives were lost, families were shattered, and the city felt the shock in its bones.

I didn’t come to photograph tragedy. I came because I needed to see Paris again — not only as a postcard, but as a place that had been wounded and was still standing.

Seeing beyond the “pretty Paris”

For years, my camera has been drawn mostly to the beauty of Paris — the bridges, the monuments, the river, the light. Those images still matter to me.

But on this trip, I realized I haven’t always paid enough attention to how the city lives — and how it responds to challenge. Paris has faced many: from the German occupation during World War II to more recent acts of terror. Each time, it absorbs the shock, mourns, and somehow continues.

I’m sharing these photographs now, years later, because I’ve come to see that my work has often focused on the surface beauty of the “City of Light.” This visit reminded me there is another Paris — one shaped by memory, resilience, and everyday life.

A walk to the Bataclan

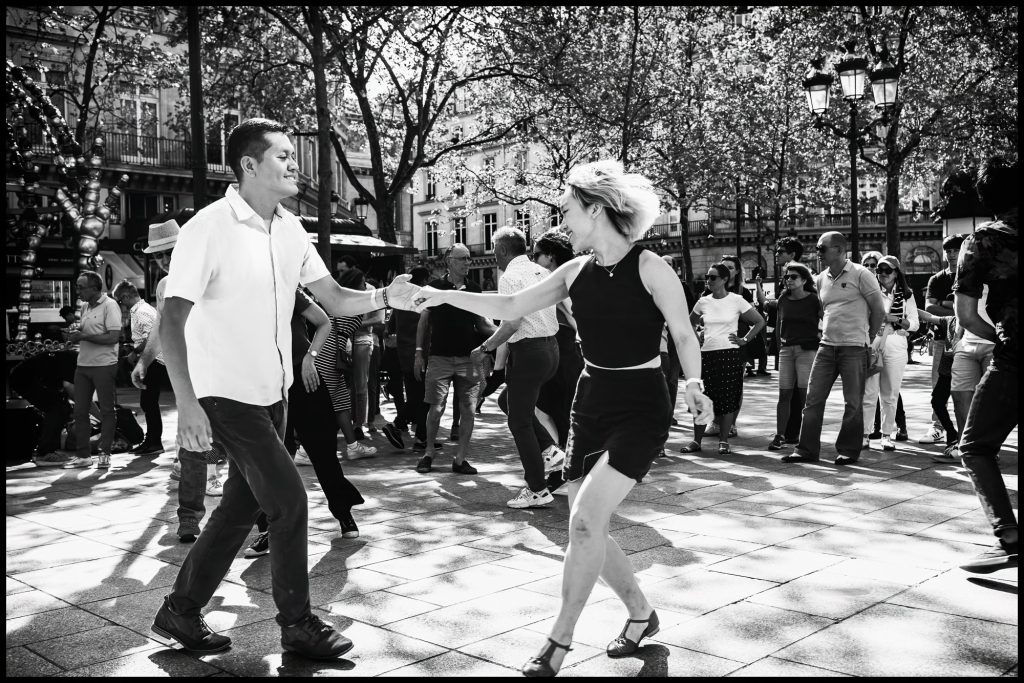

Walking toward the Bataclan, the surrounding streets looked surprisingly ordinary. Cafés were open. People carried groceries. Traffic moved as usual. And yet there was a quietness underneath everything — as if the city were speaking in a softer voice.

Outside the Bataclan, the mood changed. Barriers remained in place. Notices were taped to railings. The familiar façade now carried a weight that was impossible to ignore.

People didn’t gather like tourists. They paused, looked, and moved on. It felt more like a place of memory than a concert hall.

Place de la République

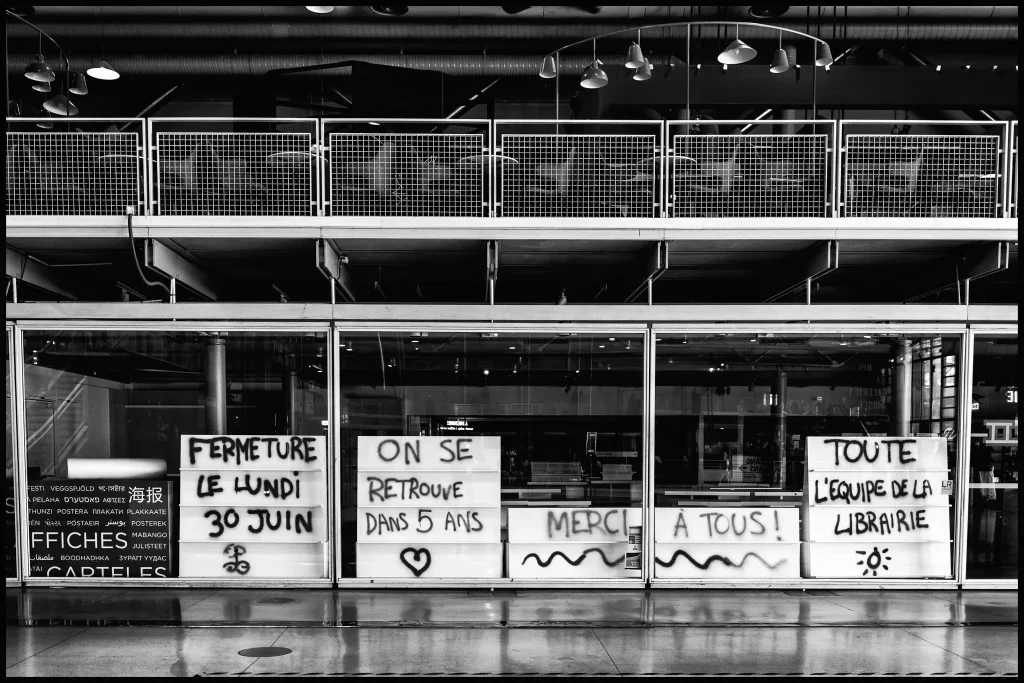

Later, I walked to Place de la République. The square had become an informal memorial — candles, flowers, handwritten notes, photographs, flags. People moved carefully, making space for one another.

There was grief here, but also dignity. The city was remembering — quietly, without spectacle.

A deeper appreciation

This visit changed how I see Paris.

I still love its monuments and bridges, but I came away with a deeper appreciation for the everyday life around them — and for the resilience of a city that mourns, remembers, and keeps going.